I used to feel like basketball was more than a game, almost like it was a person or a best friend. Growing up in a household where emotional tsunamis were common, the sport became a safe haven that allowed me to escape inner turmoil and be free in a separate identity from reality. It stayed that way in grade school and high school, feeding my soul in a cathartic way that saved me from falling into the pits of depression before I was ready.

When I pivoted from playing to writing about basketball in college, two passions were married and I thought I found a way through my career to stay close to the game that resuscitated my life in childhood.

Then Dad died.

I had an old friend compare their college playing career concluding to a breakup or divorce. When I stopped playing in high school, I never felt that. I just felt like my round-shaped best friend was morphing into a new version of support in my life. But when my Dad passed I felt that severing in full force. He was my No. 1 fan, the screaming guy who always cheered me on in the stands, the one to shovel the driveway and rebound both my makes and misses, the proud parent who’d cut out my newspaper articles to show them to his family and co-workers.

For a while after he left, I hated basketball. Absolutely hated it.

Then in 2017 I found a way to reconcile with the sport. I started coaching grade school basketball at Audubon Elementary School in my neighborhood of Roscoe Village in Chicago. I didn’t know what I was getting myself into, but I was following my heart as a compass.

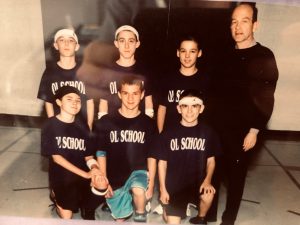

I was hired to coach both the 5th/6th and 7th/8th grade teams by an assistant principal who listened to my pitch on a cold call, and eventually I was managing about 20 kids for practices and games during the winter months. I can still remember the adrenaline from first time I blew my whistle in practice and the jitters before the tip of my first game as a head coach.

What transpired over a three-year span was rekindling of a passion and discovery of a calling in the same vein. I started to love basketball again — feeling like I got a long-lost friend back — while at the same time guiding kids with a natural muscle of leadership that had been waiting to blossom inside me.

I was never given an assistant coach but I always kept a seat open for my Dad on our bench (players knew not to sit in the empty chair next to Coach). He was there with me in spirit for the ultimate highs (upsetting the powerhouse team on the North side my second year) and the ultimate lows (losing a last-second game to a team we should’ve beat and blaming myself for game management).

More than anything, it was just the day-to-day interactions with the kids that filled my heart in a profound way. I’d have players lined up before and after practice trying to play me 1-on-1. The “Coach Gleeson watch this” and “Coach Gleeson can you help me with this” chirping still echoes in my head.

At the end of last season, my best player (who just so happened to finally beat me in a 1-on-1 battle to win Bulls tickets for the whole team) asked me which was my favorite team to coach in the last three years — a valid question considering my first year coaching I was blessed with a dominant 8th grade team that only lost one game (our best player could dunk) and then my third year the team reached the city playoffs championship game after winning the Division. The question didn’t prompt an answer so much as it prompted a sense of gratefulness.

I’m undoubtedly feeling that gratefulness now nearly a year later. Sometimes it takes something going away for us to grasp the true meaning it’s had in our lives. The emptiness I’ll be feeling this winter is less of a sadness that I won’t be able to coach in Year 4 because of coronavirus, as I’ll deeply miss coaching the 8th graders I started mentoring as small 5th graders in their final grade school season. It’s more of a reminder for the void that coaching filled in my heart over the last three years and just how much that sense of identity grew me as a man to be where I am today.

There’s an unbelievable sense of inner peace that comes from helping others — especially kids — and guiding them at where they’re at in their life journeys, no matter good or bad and all the emotions they experience in between. I’ve had kids cry and yell in defeat, fight then laugh, and embrace in triumph while coaching them. I’ve had a kid say the school should “fire the coach” when I benched him. I’ve had a kid suggest I had filled a hole left by his absent father after two years of coaching. It’s all been God’s work fueling them and fueling me simultaneously.

Yet I’m most proud of the principles and lessons taught through the sport that are indicative of life: Working together for a common goal, trusting in your teammates/friends, finding confidence and inner purpose when insecurity or apathy once seemed poised to take over. Most importantly: fighting and persevering with a mentor lighting the resilience pathway.

The past summer my grade school and high school basketball coach, George Limperis, died of cancer and it made me think about the impact he had on my life. I’d use his same drills in my practices but more than anything I thought about how he believed in me when no one else — including my own parents — could help me. I can tell that being a coach and teacher is a fraction of what it takes to be a parent, but it’s a blessed and privileged role nonetheless because it can serve as a vessel for strength (and healing) that sometimes can only be reached through that coach-player connection.

I had the experience of my Dad filling both parent and coach roles when he was my coach briefly for a travel team in 8th grade. One thing I remember from that experience was that he was always wanting me to play shooting guard and I instead wanted to play point guard. I wanted to control things, to help my teammates and let them do the scoring while I’d do the assisting as the captain and pilot of the team. He wanted me to release control and let my teammates help me and be more of a free spirit to score on the court. Of course, as my Mom can attest to from our joking family arguments growing up, my Dad was always right. Even though I got my way back then by playing point guard, he was right in this case. Though it didn’t take shape until long after my playing career ended, now all I do is shoot in pick-up games and the memory of me playing point guard — for others — feels long gone. It’s annoyingly evident that shooting and scoring was just waiting to come out in my game.

But I think the compromise I’ve made with my father comes now with coaching — a far more natural fit. In this identity I can help others and lead, while at the same time releasing control because I’m not out there playing myself.

This compromise feels like a metaphor for life in that having patience and passion can lead to fulfillment. Mastering that balance is the challenge.

During quarantine I watched this show Cobra Kai, a spinoff from the Karate Kid franchise. In it, one of the main characters, Daniel, reflects on his relationship with his since-passed mentor Mr. Miyagi (the wax on, wax off guy). Anyway, one of the takeaways from his fallen mentor is to put good into the world and good will come back to you. That good from the last three years of coaching has come back around as I’m missing it.

I don’t know if I’ll get to coach another season because life is unpredictable in that way and I don’t know what 2021 and 2022 will bring. But I do know in this very moment I’m feeling eternally grateful for coaching kids I’ll always remember and for having a three-year chapter of my life filled in such a meaningful way. 2020 was a trying year for a lot of us where a lot of things didn’t go the way we had hoped or wanted, but I know that as I turn the corner on this new year, I’m feeling the permanence that’s come from a form of identity I am indebted to.